Should Central Banks Want Unemployment?

This week's trending economics news narratives, in summary, in context.

📰 Trending News Narratives

Economic news narratives, in summary and context.

Should Central Banks Want Unemployment?

The biggest story this week across several markets is the ongoing debate about the role and goals of our Central Banks.

In the US, Democrat Senator Elizabeth Warren’s questioning of the Fed chairman Jerome Powell drove at this question - “What do you say to the 2 million families who will be put out of work by your plan?” and, equally as important, once unemployment starts climbing, how do you stop it? (Hint, they historically found this very difficult).

Powell responded that “[unemployment is] not an intended consequence”, but I have yet to hear any central bank articulate a consistent or compelling position on what they believe about what role employment rates should play in inflation reduction. Do they believe it is regrettable but necessary? Do they hope they can raise interest rates without causing unemployment, or is that an important causal factor for getting inflation under control?

I have argued that Central Banks should want to get people out of the wrong jobs. Jobs that were only created because an abundance of cheap credit allowed jobs to exist that didn’t make the most productive use of their time. Job transitions are never easy, but there is no better time to do this than now, when there are still a huge number of job openings. Moving people from underproductive employment to productive jobs will help increase the economy’s productive capacity and alleviate our supply constraints, thus easing inflation.

But I don’t hear this articulated, or any positive framing of their agenda beyond a vague notion that we have to take our medicine and suffer an increase in unemployment.

Employ America: “The Fed Is Trying To Engineer A Recession” Link

Bloomberg: “Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s testimony ripples across markets” Link

Kayla Scanlan: “Labor Market vs Inflation” Link

Do We Hate Share Buybacks?

In the US, as part of implementing the CHIPS Act (industrial strategy aimed at promoting domestic production of microprocessors, and many other things) the Biden-Harris administration have said that the US Government will “evaluate applications based on the extent of the applicant’s commitments to refrain from stock buybacks.”

This follows on years of campaigning by Democrat senators Bernie Sanders, Chuck Schumer and others calling for restrictions on stock/share buybacks, a process by which corporations give spare money back to shareholders by buying shares from them.

Most news stories covering this trend are comparing buybacks to dividends (they’re functionally equivalent) and pointing out that both are neutral tools, sometimes good, sometimes bad. Warren Buffet even used his most recent shareholder letter to make this point:

“When you are told that all repurchases are harmful to shareholders or to the country, or particularly beneficial to CEOs, you are listening to either an economic illiterate or a silver-tongued demagogue (characters that are not mutually exclusive),” Warren Buffett

I agree with this point, but I think the analysis is missing the wood from the trees. The bigger picture question, and the one I think Biden, Sanders and Schumer are picking up on, is how we distribute the gains from broad productivity increases?

In a simple model of capitalism, companies and industries grow richer as productivity improves. How does this benefit society? We all naturally benefit as consumers. More is produced for less, which usually results in wider choice at lower prices.

But how do we benefit as workers? We certainly want a capitalism that incentivizes productivity increases, so gains should flow to someone. Is that shareholders alone? Probably not. As productivity increases in an economy, we should also want benefits to accrue to society as a whole.

These attacks on buybacks are best viewed as a crude mechanism to push for that. If the benefits can’t all accrue to shareholders, some of the spare cash may go to wage increase, or more generous leave or other ways to distribute benefit in ways that reward all of the stakeholders of productivity improvement.

NYT: “The Case Against (Some) buy backs” Link

WSJ: “Warren Buffett’s Slap at Buyback Illiterates Rings True” Link

Noah Smith: “Stock buybacks don’t really matter” Link ($)

What is really driving inflation?

In the US “Corporate Greed is Causing Inflation” has become the most cohesive narrative to counter the notion of a “Wage Price Spiral”. The first suggests that an imbalance of supply and demand gives companies the opportunity to hike prices to make high profits at a time of scarcity. The second suggests that the costs of inputs (including wages) are forcing companies to pass on price increases against their will.

Leaked discussions from the European Central Bank “showed that company profit margins have been increasing rather than shrinking, as might be expected when input costs rise so sharply”. The need to use interest rates to get wages and costs under control has been the dominant narrative, but the data suggest that “corporate greed” is the more accurate one. Link (Reuters)

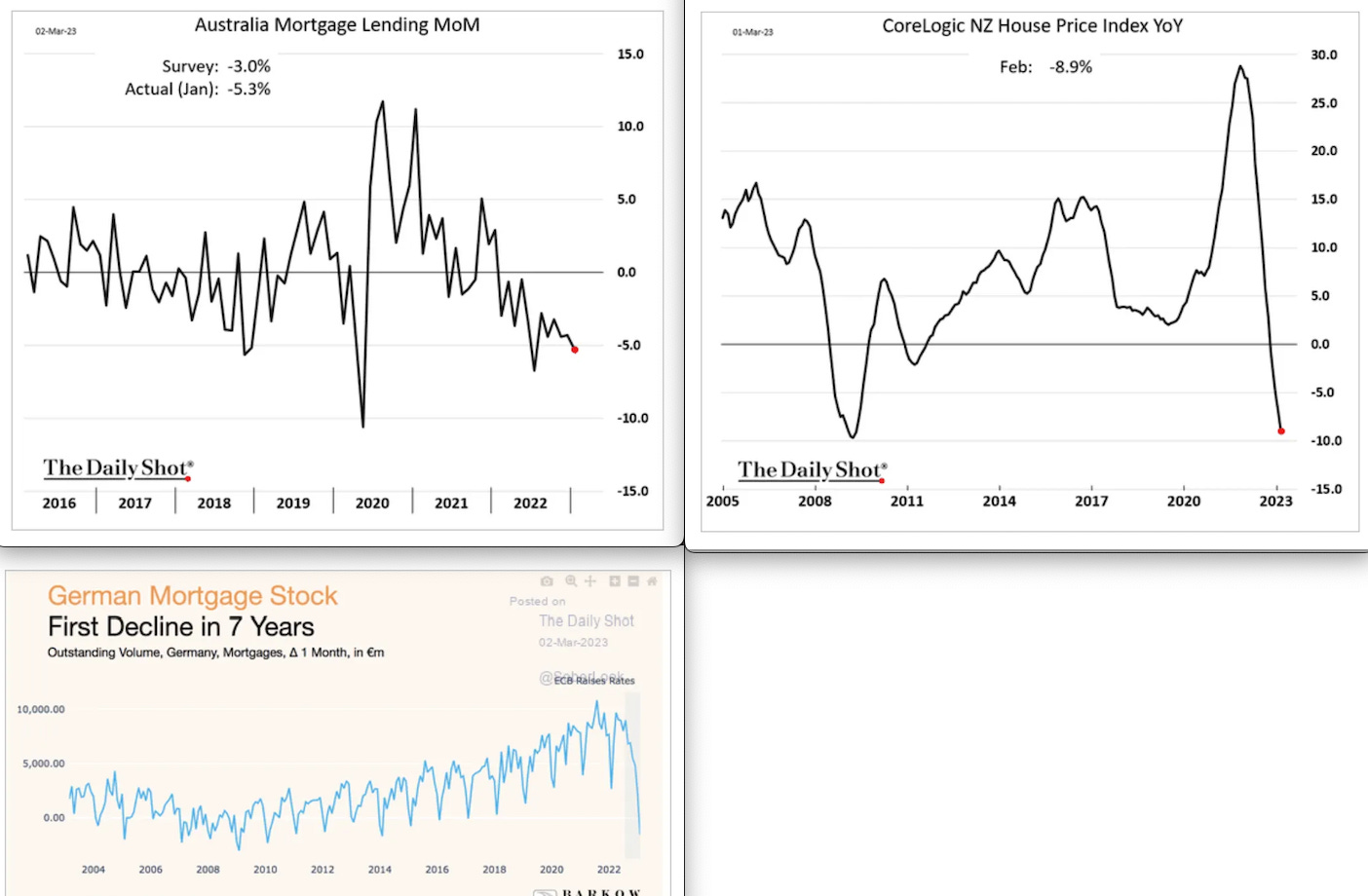

House Prices are Falling

Here’s a snapshot of housing graphs from across the anglosphere.

In almost all markets, as interest rates rise, house prices are starting to fall. I’d expect some new narratives to emerge around this as the year progresses.

In general, property has been a very powerful tool to create the middle class wealth since the mid-1900s. Through land ownership, average people had a very literal ownership stake in country as a whole, and benefitted as the country grew rich. A significant avenue for productivity growth to accrue to the middle classes.

Unfortunately this value is only realised when they sell that home, which now means selling it to each other's kids and grandkids at steeply inflated prices.

At it’s core, the story of land and property is evolving from a political tool of middle class wealth building to a story of inter-generational wealth divide and conflict. It will remain that way until we start building housing at scale again.

📊 Public Opinion

Research and Data on people’s economic beliefs.

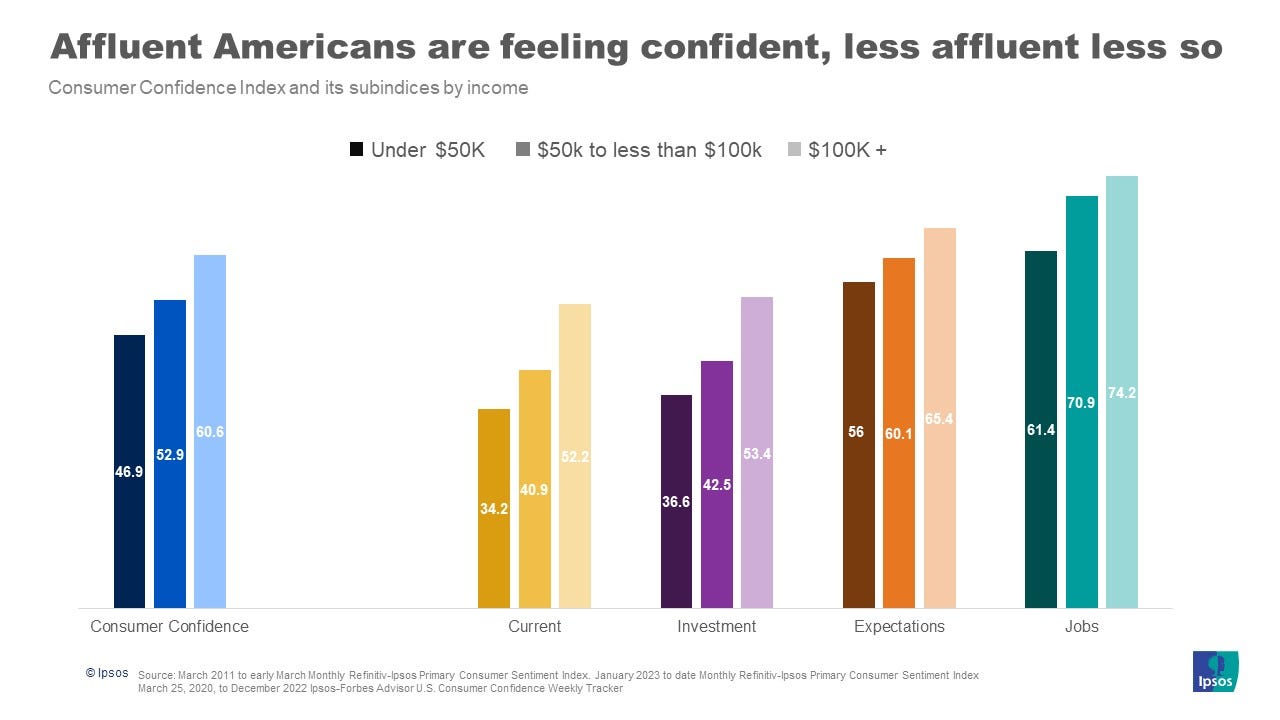

Inflation is Regressive. In the US, people’s confidence in the Economy is heavily dependent on their income level. With inflation driving costs like fuel and rent, it is hitting the poorest hardest. Link.

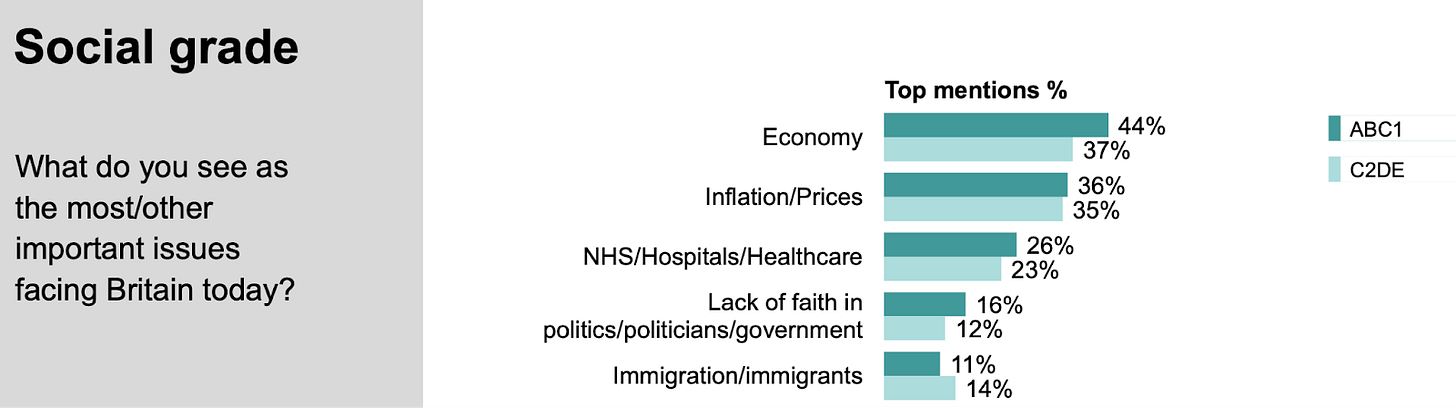

By contrast, this is not true in the UK, where wealthy people are slightly more worried about the Economy (Brexit driven, presumably) and equally worried about inflation. Link (PDF)

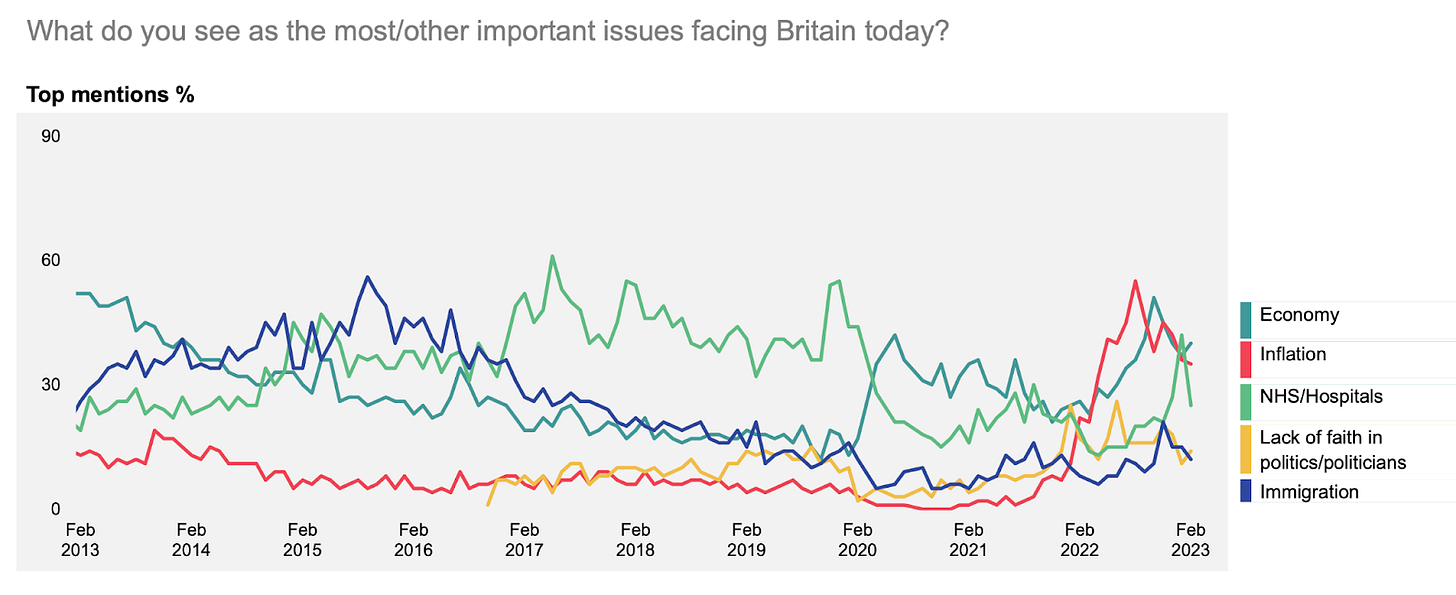

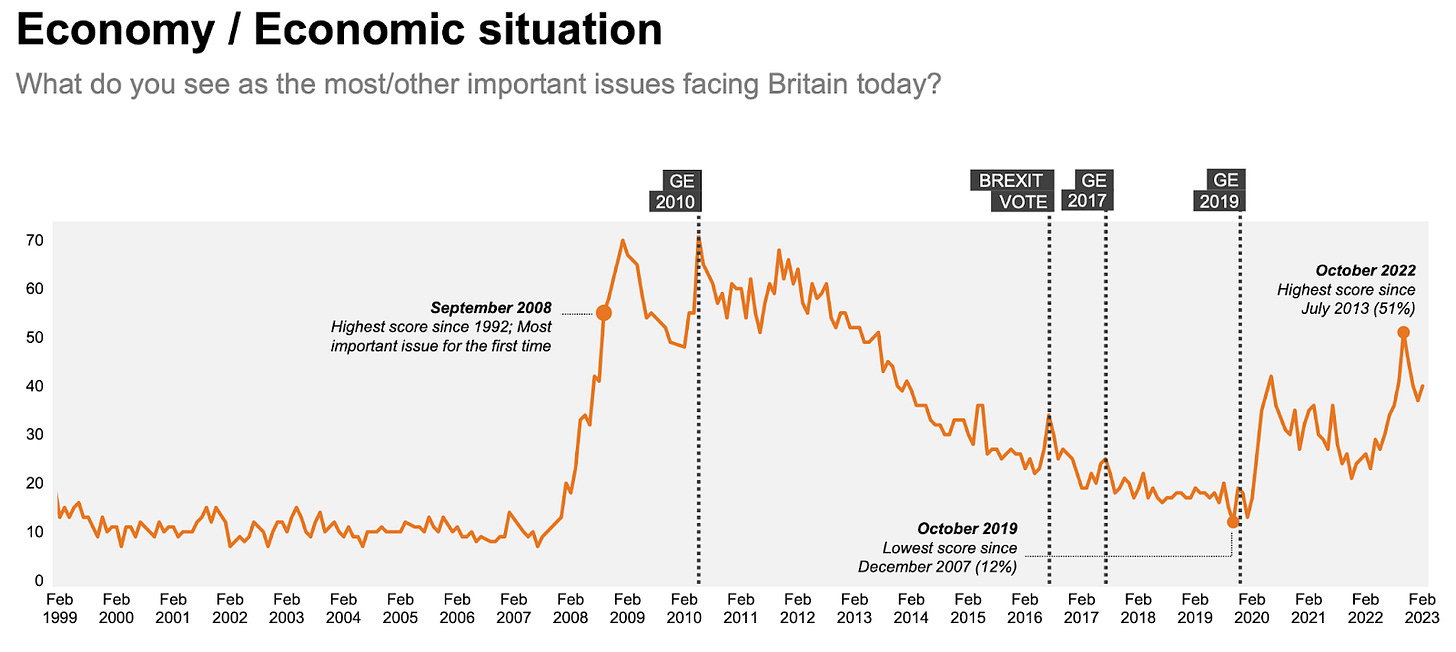

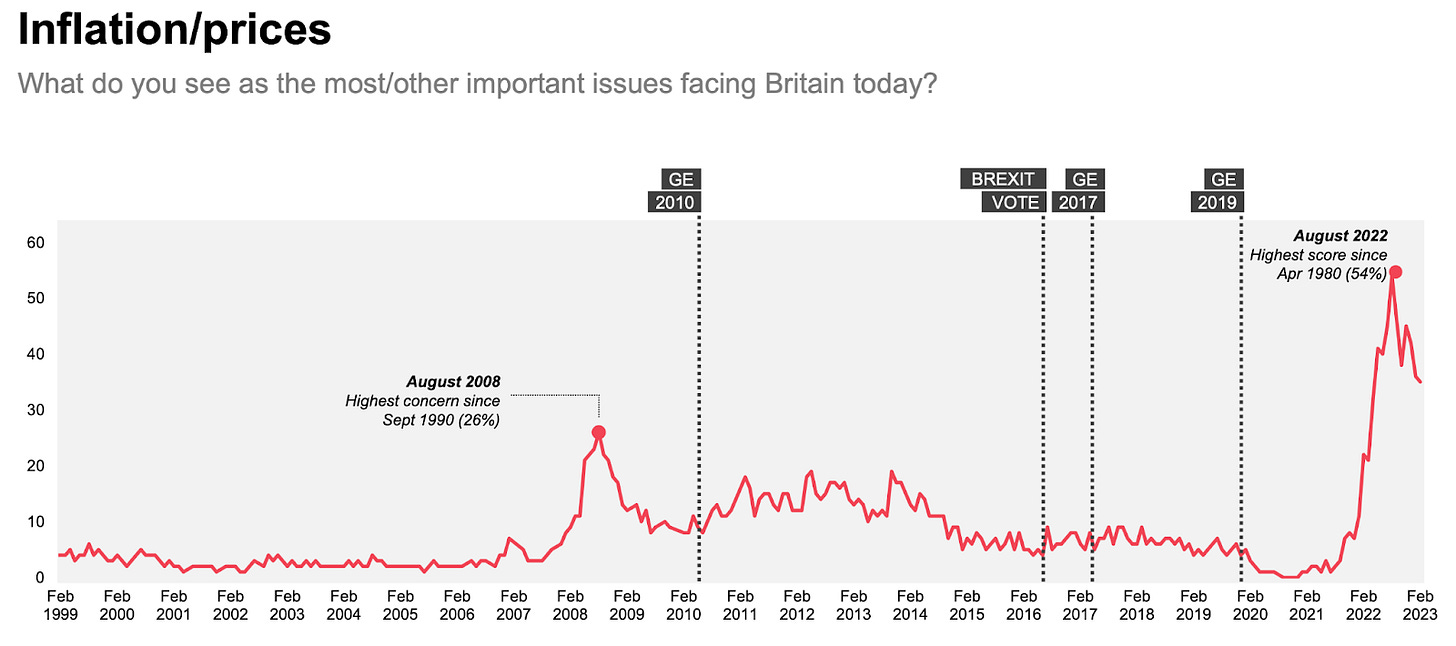

UK Economy. In the UK, the Economy and Inflation remain the top concerns for voters, replacing the NHS after a winter spike in January. Link (IPSOS)

As the graph above shows, “Economy” has ranked consistently high as a concern since the outbreak of COVID-19, but inflation climbed steadily throughout 2022, peaking in the winter.

Zooming in and zooming out, worries about the economy are at the highest sustained levels since the great financial crisis:

Worries about inflation haven’t been this high since the 70s, though they seem to be on a downward trajectory: